Blue, Blue Christmas

The Unusual Holiday Scent That Gives Me All The Feels

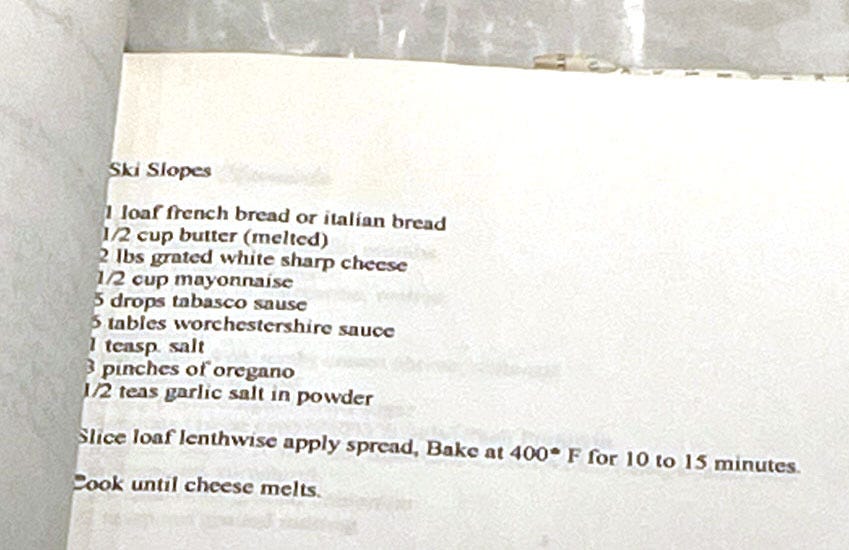

At long last, it’s Christmas Eve. The hum of the electric can opener temporarily drowns out the carols playing on the tape deck radio in the kitchen corner. Mommy is making shrimp dip, a signature element of the evening’s festivities in our house, along with canned ham, grasshopper cocktails, and a cheesy garlic bread-like concoction she referred to as Ski Slopes. I stand over a register in the living room floor where dry smoke-tinged heat rises. The furnace rumbles in the cellar beneath me. I adjust my foot to cover the metal register so I can absorb more warmth. Paper towel in hand, I part the frilly curtain and blast the window in front of me with bright blue liquid. I wipe away the runnels of gray to reveal the snow-covered rose bush outside. I inhale deeply, and sigh. This is the holidays. The mingled smells of baking ham, peppermint, and cleaning, ahhh.

We cleaned so infrequently that, to me, the scent of Windex reminds me of Christmas.

In the Eighties and early Nineties, high-end “artist” teddy bears were all the rage, and my mother was one of the trend’s superstars. A Brenda Dewey bear might sell for hundreds of dollars. She traveled the country (and the United Kingdom) selling her fully costumed “soft sculpture” wares at trade shows, designed Ashton Drake bears hawked in magazines, and earned the cover spot on several bear calendars sold in bookstores nationwide. Brenda was, like me, an early riser, up before sunrise and cutting mohair fur from her patterns, fueled on Folger’s coffee and packs of cigarettes. She toiled in her sewing room until after midnight to fill huge orders from galleries. She was a one-woman business as she felt that no one else could infuse her bears with life. “Every face comes out different,” she would say, and I agreed.

Though my grandfather had always advised her to “get a real job,” she rose to great prominence in her field and, eventually, earned a decent income from her art. That’s the artist’s dream, right?

Fame and fortune have costs, of course. As Soda Fountain Bears and Cosmic Nites (her successive teddy bear DBAs) took off, the immediate cost was motherly duties. She was still our mom but many of her typical parental chores fell by the wayside—and, I believe, she was secretly grateful for the excuse to shed the mundane drudgery of the twentieth century housewife. Dinner on the table by six every night? Dream on. Clean clothes for school each day—who has time for laundry? (Not that we had the machines, or the water, to wash clothes in our own house.) Cleaning—why bother? These three boys and their mechanic father, plus the numerous cats and dog, will just make a mess anyway.

There were few occasions important enough to exert the effort to clean. About once a year, Mommy caved to pressure from her sister and hosted a Tupperware or candle party. Another was my family’s annual Christmas Eve gathering. Mommy invited her best friend Cree and her family (of five, just like us) and her former neighbors, the Rogers’s, next door neighbors from when she and Aunt Nancy grew up on Canterbury Drive. It was her annual chance to catch up with them—Cree dropped in for coffee at least once a week, so I suppose that seeing her former neighbors elevated Christmas Eve to the “clean the house” status.

Before the guests arrived, Brenda supervised my brothers and me on performing six months’ worth of housework in one afternoon. To this day, whenever I break out the Windex to shine up our bathroom mirrors and shower door, I inhale deeply and think back to those Christmas Eves on Brimfield Street.

Not only did my mom make teddy bears, but she also collected them. Our pine-paneled living room became a bear and doll museum, and they filled multiple shelves, whatnots, and curio cabinets. As Brenda acquired more and more—“Look at that face, how could I have said no to that face?”—the older bears sank into the pile, which was the default display mode when a collection grows that large and you live in a small house with a family.

I can say from experience that fuzzy bears both attract and turn into dust like nothing else. It was a blessing that the windows were so dirty: no beams of sunlight entered to highlight the endless dancing dust motes. Brenda also loved living furballs: we always had at least one cat, and once we had sixteen. Why pay the vet to spay or neuter them? (We can’t afford to get the human kids to the doctor so why would the felines fare better?) Add their fur, dander, and, most of the time, their fleas to the mess.

She smoked incessantly, indoors, and filled ashtrays several times a day. How could we make the place dustier? We heated our house with a wood burning furnace which added who knows what kind of particulates to the air. It’s amazing that none of us developed allergies or asthma though surely that is due to pure luck. The jury’s still out on lung cancer. My mother made only one concession against the innocence of her smoking: my brother Brian was born two months early and had to be incubated until his lungs strengthened. She had smoked throughout pregnancy just as she had done since age sixteen.

One spring, my mother achieved a life-long goal and owned a horse. She named him Smokey, because he had a light gray coat and she was going to afford his stable and board fees by quitting smoking. She didn’t. When on a riding lesson in the woods behind our house, Smokey jumped a fallen tree and Brenda flew off. She landed on the log and tore a ligament in her leg. She was in the hospital for a week, in traction. When my dad brought my brothers and me to visit, the nurses’ heads swiveled. “I smell a fire! Where is that smoke coming from? I don’t see it but I smell it.” In the antiseptically clean environment of a hospital ward, the woodsy, ashy aroma rolled off of our clothes and bodies. “My God, is that how we smell?” Brenda asked from her bed. Because we marinated in it all day, we were nose-blind to it then. Other people buy candles and room sprays that are supposed to smell like a cozy burning log and I gag. Just the idea that smoke scent makes people feel cozy is wild to me. The current trend of infusing cocktails or meats with wood smoke? You can miss me with it.

Instead, I’m seeking a candle that smells like streak-free window cleaner. In preparation for Christmas Eve, I pulled aside the frilly living room curtains to blast the casement windows with spray and paper toweled them dry. In the kitchen, my mom blended canned shrimp with softened cream cheese and cocktail sauce. “Scott Rogers loves my shrimp dip,” she bragged. “I told him, it’s easy to make, but he says he waits all year for me to make it!” It was the era of quick “semi-homemade” recipes in magazine ads, what can I say.

Around four o’clock, she skewered canned pineapple rings and maraschino cherries onto the ham with toothpicks and slid it into the oven to bake while she scrubbed half a year’s worth of toothpaste drippings from the bathroom sink. More Windex for the mirrored medicine cabinet, whose gold colored paint flaked off more and more each year. After her pass at our solitary bathroom, I sneaked in and performed my own ritualistic decluttering. Mommy was also fond of piles of jewelry, cosmetics, and perfumes, and this tower teetered precariously right next to the toilet. I tossed the majority into Ziploc bags and stashed them under the sink just to present our ‘seated’ guests with something close to a clean surface, lest they knock blush compacts and beaded necklaces into the dark, dank gap between the toilet and the tub.

This was long before Marie Kondo. If her philosophy had been around in the Eighties, Mommy would likely said that each and every object in her piles sparked joy. She was a maximalist. Oh who am I kidding, she had hoarder tendencies before hoarding became cable TV show cool. I can’t watch those shows. It reminds me of home too much.

Besides, I can simply clean glass anywhere in my home and think back to Brimfield Street! Don’t get me wrong, there are plenty of other scents that say Christmas to me, like when I bake Mommy’s molasses spice cookies, which she called gingerbread. She also made brownies (storebought mix of course) and customized them by adding peppermint oil. Sometimes she topped them with chocolate frosting and crushed candy canes. Each year we decorated a live tree cut down by hand from one of the countless Christmas tree farms nearby, and the holidays always came alive when we brought the evergreen into the house.

My mom loved cinnamon as well, and though she did not have time every year, she often made potpourri-filled lace and satin ornaments for the big wooden hutch in our living room. She put her ceramic church and skating scene, complete with a mirror representing a frozen pond, on its waist-high counter, and strung garland, lights, and potpourri bags around its top. Though it caused her hands to burn and itch with a nasty red rash, she enhanced the potpourri with fresh cinnamon sticks and fragrant oil. She added ribbon rosettes, bows, and more lace for a fringe. They were very Eighties country—she probably drew inspiration from a photo shoot in Country Living, Good Housekeeping, or another of the magazines she picked up on a trip to Sew Fro Fabrics.

We all know that our olfactory sense has the best connection to memory, and we were a fairly typical family who filled our home with peppermint, cinnamon, and pine tree at holiday time. Most people who celebrate the holiday associate those smells with warm memories of home (even if that was not your actual experience, and if this applies to you, I wish you happier celebrations ahead).

Though I never asked my mom why she sought out those fragrances, I imagine they reminded her of Christmases past, from her childhood in Vermont or teenage years in New York. I bring them into our home for current holidays because they’re classic scents, and they bring me comfort and joy. I don’t intend to imprint these scents on my children’s memories. If it happens, and it causes them to fall into a pleasant remembrance, great.

Like a lot of holiday traditions, we share them with millions of others in a way that politics, ideologies, religions, or income levels fail to achieve. We do not have much control over the connection between smell and memory, though, and one scent you find comforting may stir anxiety in someone else. I know my mom did not think that the smell of Windex would overpower her love of classic holiday smells for me. It just happened.

It’s one small but unique gift my mother gave me without realizing what she was doing. This scent memory is something special that brings those Brimfield Street holidays back to me with amazing clarity. Call me quirky for being nostalgic for holidays gone by when I smell Windex. In reply I say, Merry Christmas.