Nary A Drop To Drink

Growing up in a home without drinking water and occasionally no water at all.

When I tell my children about my childhood, which is “the stone age” to my freshman son, they often think I’m making up a story and they say “stop the cap.” Sometimes adults get a strange, questioning look on their faces, as the environment I describe contains some details that don’t jive with the Seventies and Eighties. My childhood sounds like an amalgam of Little House on the Prairie (which I devoured in book form and watched on TV) and the Great Depression, which had a massive impact on my paternal grandparents’ lives, mentalities, and offspring (my father).

“These kids are so lucky, and they don’t even know it,” my husband and I often say, usually after we’ve served them a delicious meal using ingredients fresh from our garden. That phrase comes back to me on some evenings when I draw our eight year old’s bath, because when I was growing up, we didn’t have unlimited water, and certainly no tankless hot water heater to keep us warm in the winter too. We had running water, but we had to ration it, and it wasn’t potable. Water was so scarce that we could not take regular baths. Or showers. I wish I could say it was due to conservation efforts that blossomed in the early Seventies, but no, it was out of necessity.

High school sweethearts, Albert and Brenda married and had a kid (yours truly) young, as was often done in those days, and lived with my mother’s parents on Canterbury Drive. Both of them grew up in Clinton, NY, a small, quaint town with New England overtones: a village green, a cider mill, a small private college, and dreams of ice hockey greatness. My dad was a mechanic at a small garage, and my mom became a housewife with foiled artistic dreams. As young marrieds on a single income, money was tight, but they needed to move out of Mom’s old bedroom and get a place of their own. They purchased an old two-bedroom, one-bathroom house on Brimfield Street when I was just a toddler. Purchasing price: $9,000—affordable for a “starter home” “fixer-upper” if by “starter” you mean ownership over the next twenty years and “fixer-upper” means “never finished.” And “affordable” means “barely within reach.” Other factors in the price: the house relied on a shallow well for water, a wood-burning furnace for heat in the lake effect snow belt, and insufficient insulation. The previous owner rented it out to college students, who painted a few walls in psychedelic hues, but the place was originally constructed in the early 1850’s. Family lore says that our house had been part of an estate, the main house of which had been demolished and its grounds turned into a cornfield, but I have not verified that fact. I appreciate the story, though.

Because the house’s age, and lack of certain modern conveniences, my family of (eventually) five practiced the fine art of “if it’s yellow let it mellow.” Pause here for groans and disgusted faces. We had a tub, but no elevated shower head. The tub was, we suspected, an antique claw foot that had been boxed in, probably sometime in the 1930’s when Victorian fell out of fashion. We shared that one bathroom for years., until the summer before my senior year of high school when my dad built an extension on the house and installed half a “master bath” that, as mentioned before, was never finished.

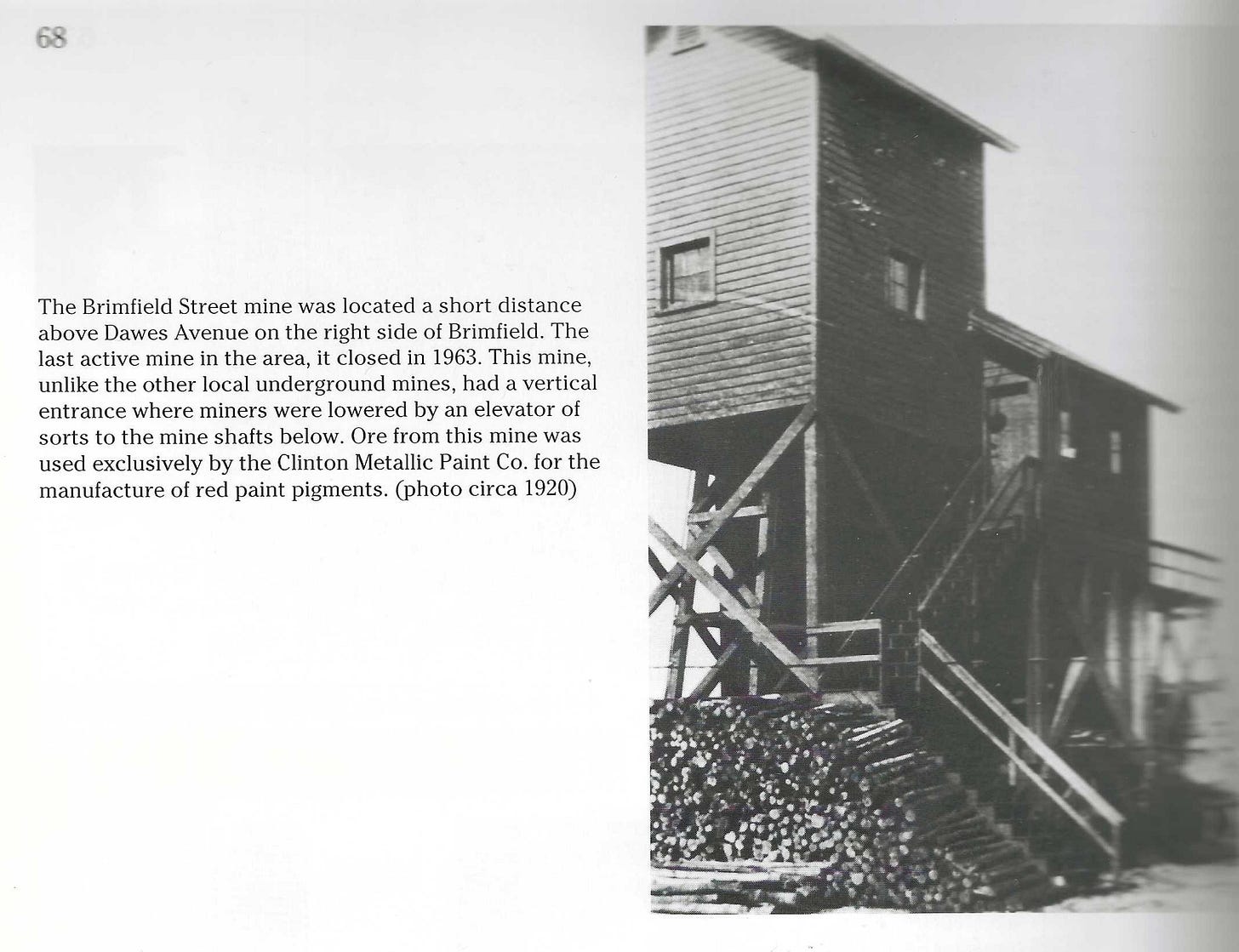

Our little neighborhood—a collection of seven houses surrounded by cornfields and woods—sat on the fringe of hilly terrain that rose to Paris Hill. Brimfield Street ran from the heart of the village itself, where houses enjoyed town water, all the way to the town line. We lived at the top of the first lump in the hill, just above what was then a truly precipitous climb, even for cars. Properties after that first hill relied on other sources for water. “The hill’s too steep to pump water up there,” people always said, the same excuse we heard about the lack of cable TV. Families and farms relied on wells for water. Our little collection of former outbuildings, at the top of the first big hill but tantalizingly close to town, had been built over old iron ore mines. My aunt Alma gave me a book of old photos of our village, and in these you may catch sepia-toned glimpses of the mining company buildings, shacks, and mine cart tracks for exporting ore. The mines on Brimfield Street used to be world-famous (in a world now long-gone) as the source of much-needed Clinton iron ore, a valuable resource used to make red paint. Every time I see a beaten-up barn with flaky red paint I wonder if it had been painted with Brimfield Street ore.

Pages from Clinton: A Glimpse of the Past, 1987. The house I grew up in on Brimfield Street sat just east of Dawes Ave.

The long-term effect of the mining operation, aside from leaving deep gouges in the landscape that had filled in with forest over time, was that the water table under our land was extremely low (note the use of the word “honeycombed” in the photo caption above). The well on our property, which we shared with our next door neighbor, was too shallow and ran dry soon after the springtime runoff. The theory (family lore again) was that the mine shafts, which wiggled through the earth beneath us, provided very efficient drainage, so our shared well provided only a few weeks’ worth of water each year. Digging a new well, or drilling deeper into the existing one, would be futile, and expensive far beyond our means.

That’s what they told us, anyway. I can’t verify any of that, other than the existence of the mining operation and the tunnels. Most of the shafts had been capped, but we knew of a few open ones. They were easy to spot. Steam would rise from them in the winter, since the air was colder than the ground, and all you had to do was follow the vapor trail. There was one down next to the pond on Dawes Ave, and another in the woods, in one of those excavated trenches now covered with bushes and trees. As kids we often made plans to gather flashlights and rappel down the shafts with ropes, just to see what we could see, but we always chickened out. A little bit further away, also swallowed by the forest, we found old cooling tanks and foundations from mining structures. These overgrown sites seemed to be straight out of adventure movies (Indiana Jones and Goonies specifically, according to my young mind). I remember one of the cooling ponds completely covered in thick neon-green algae, or moss, or slime. Something only a botanist or a mad scientist could love. I only knew I didn’t want to fall in and really find out.

Summer’s heat always coincided with the well running dry, which meant that our family and our neighbor had to rely on cisterns. Rainwater ran across the each roof, trickled down gutters and drainpipes, and flowed into large, dark, cement basins in our cellars. These open tanks were more like five-foot-deep pools lurking underneath our feet. The walls came within a foot or so of the (very low) basement ceiling, so I could stand on tippy toes to peer over the edge and check on the water level at any time. My dad also explained, probably when I was far too young to learn of such things, why we could not drink the water. Aside from the completely unsanitary surfaces the rain water traveled over to reach the cistern (roof, open gutters, downspouts likely choked with leaves and debris), animals both mammalian and insectoid could and surely did come into contact with the water. Dad told me that he watched a mouse run along the edge of the cistern which tripped mid-scamper and plopped into the cool, dark liquid. “The bottom of this tank probably has a layer of leaves, sticks, mud, and bones you wouldn’t believe,” Dad said. Except I did believe it, because I saw what happened when the cisterns also ran dry. Black, stinky muck gasped and spat from our faucets during those dry, hot, painful summers.

The untreated, unfiltered water could be used for cooking, cleaning, and washing, but even my parents had the sense (and taste buds) to forbid consumption of it. We drank from a giant yellow plastic McDonald’s “bug juice” cooler, with a red lid and a white spout, which sat on our kitchen floor. To access the water, we would yank off the red lid and ladle out enough to fill our cups, or, more often, we’d dip a Tupperware pitcher right in. Grammy sold Tupperware so we had plenty of plastic storage containers of all kinds. Dip the pitcher in to fill it, tear open a packet of Kool-Aid, and dump in two whole cups of sugar. That’s what we drank—or milk, and lots of it. But what options did we have? Frozen juice, yum. My dad often opted for canisters of Five Alive concentrated mix since that was cheaper than Minute Maid or other name-brand orange juice. He was all about Five Alive, which I despised.

We drank so much milk—when we got older, we came close to consuming a gallon a day. And this was before 2% milk. Skim was available but only health nuts, like my Aunt Alma, bought that. We never had to worry about weak bones or calcium deficiencies. To make it even better (or worse depending on your viewpoint) we mixed up some super-strong chocolate milk. In step with the Kool-Aid, we bought jumbo containers of Quik, back when they came in tin boxes with a circular pop-off lid. I always spooned in so much chocolate powder that I could spoon up a thick slurry of deliciousness from the bottom. I remember one day my friend Benjy arrived at our house to find me sitting on the front porch, slurping down chocolate sludge. “I knew you’d be doing that,” he said.

“What do you mean?”

“You and your family are always drinking chocolate milk with a spoon, every time I come here.”

He wasn’t wrong: I just resented the implied source of my pudginess. (As you can likely guess, I was an overweight child.) Benji’s mother only added half a cup of sugar when she made a pitcher of Kool-Aid, if she made one at all. To my highly attuned taste buds, it wasn’t even worth drinking—worse, perhaps, than Five Alive. But his family had a well with delicious water and could shower or bathe every day.

I recall a few dips in the tub, but we usually took sponge baths with our unpleasant-smelling water and a bar of Dial. Filling the tub, even once a week, was too great a water luxury to afford lest we run dry. When that happened, and it did regularly during my elementary school years, the town fire department would be summoned to fill the cisterns. I remember what a ruckus those fire trucks caused in our neighborhood. All six of the neighbor families trooped over, looking for a blaze, only to be disappointed when my dad told them the crew was merely refilling our cisterns. I don’t know what favor or story or plea had to be told in order to get this sort of assistance. In later years, the fire department stopped performing this free service and advised my dad to call a pool water company. “Pay for water? They’re nuts!” In his mind, that would be as crazy as paying for heat in the winter, or, God forbid, air conditioning.

Once—I remember it, but Dad denies it—during one drought, we went over a week without running water. Maybe the fire department was also out of water. We kids were always ripe-smelling, oily little creatures since we couldn’t take baths at home, but that summer was especially bad. When the drought finally broke in a heavy, needle-like deluge, my dad grabbed the soap and ordered us out into the front yard. “It’s nature’s shower, now get clean!” he said. My brother Brian and I protested, as we certainly didn’t want to strip down naked in the yard. After several minutes of angry looks from Dad, we doffed our shirts and washed at least half our bodies with yellow suds.

The other solution often employed those summers was to take us swimming. My mom had a friend with a pool—in a true suburb of Utica—to which we escaped on rare, luxurious days that made me feel like Annie arriving at Daddy Warbucks’ mansion. Mostly, we went to Aunt Nancy’s house and enjoyed her above-ground pool with our cousins. It was yellow and blue, like a circus tent. As she was (and is still) a bit of a neat freak, she cringed as she watched us sully her perfectly clean pool even though she set up a kiddie pool at the bottom of the ladder to rinse the grass, dirt, and rocks from our feet before we were allowed to dive in. If we did manage to go swimming, that counted as our bath for the week.

Yes, for the week. If we got one bath a week, that was a lot. I now make my kids bathe every school night, and they resist so strongly some nights that I’m tempted to let them sleep in their filth. My second-grader actually begs for sponge baths, at which I shudder in horror (why does he like these?). He’s going for speed, to extend video game/Uno/goof-off time. My older child loves to take intensely hot showers, for forty-five minutes to an hour if we forget to set a timer. That was an unheard-of indulgence when I was growing up. More than fifteen minutes, under a showerhead, with HOT water? Get out of here. Again, he has no idea how lucky he is.

My family endured and survived for twenty years in a drafty house with insufficient water, a wood furnace for heat, half a dozen unfinished repair projects, and no air conditioning because we could not afford such luxuries. I have to give credit to my parents for successfully keeping from us all those years the secret that we were poor. While infrastructure issues like water and heat added another layer of constant stress on us, my brothers and I never felt poor. Sure, we only got new clothes twice a year (back to school time and Christmas) but Albert and Brenda put food on the table. We enjoyed birthday parties and holidays, just like our friends at school. I suppose, just as my children will learn, I came to appreciate all my parents did give us despite the obstacles. I remember these details and stories with a wry smile. As for the discomfort of lugging jugs of water into the house, the frustration of turning on the taps in summer and letting black muck flow, or enduring the teases from classmates who got to bathe regularly…now, it’s all water under the bridge.

More childhood memories from Brimfield Street coming in later essays.